The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath anointed me to preach good tidings unto the meek; he hath sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound;

2 To proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord, and the day of vengeance of our God; to comfort all that mourn;

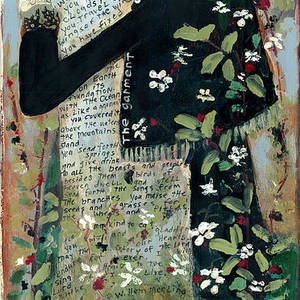

3 To appoint unto them that mourn in Zion, to give unto them beauty for ashes, the oil of joy for mourning, the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness; that they might be called trees of righteousness, the planting of the Lord, that he might be glorified.

4 And they shall build the old wastes, they shall raise up the former desolations, and they shall repair the waste cities, the desolations of many generations.

5 And strangers shall stand and feed your flocks, and the sons of the alien shall be your plowmen and your vinedressers.

6 But ye shall be named the Priests of the Lord: men shall call you the Ministers of our God: ye shall eat the riches of the Gentiles, and in their glory shall ye boast yourselves.

7 For your shame ye shall have double; and for confusion they shall rejoice in their portion: therefore in their land they shall possess the double: everlasting joy shall be unto them.

8 For I the Lord love judgment, I hate robbery for burnt offering; and I will direct their work in truth, and I will make an everlasting covenant with them.

9 And their seed shall be known among the Gentiles, and their offspring among the people: all that see them shall acknowledge them, that they are the seed which the Lord hath blessed.

10 I will greatly rejoice in the Lord, my soul shall be joyful in my God; for he hath clothed me with the garments of salvation, he hath covered me with the robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom decketh himself with ornaments, and as a bride adorneth herself with her jewels.

11 For as the earth bringeth forth her bud, and as the garden causeth the things that are sown in it to spring forth; so the Lord God will cause righteousness and praise to spring forth before all the nations.

In fulfilment Of Isaiah’s prophecy, at the beginning of his ministry outlined in Luke 4: 16-23 with reference to Isaiah 61:1-11, Jesus proclaims liberty to captives, binds up wounds of the broken hearted and gives recovery of sight to the blind, through the preaching of the good news of the gospel to the poor. He is the Word that was sent to heal us―the Great Physician. The Way of Jesus is the embodiment of the manifest beauty of the kingdom of God, in contrast to the ashes of our fallen and broken world. Jesus, is the balm in Gilead for our mourning, and he gives us a garment of praise in exchange for a spirit of heaviness. His kingdom is in our midst, and in between this pause of the already and the yet to come, now is the accepted time, now is the day of salvation. In this favourable time, he is cultivating trees of righteousness: “And they shall build the old wastes, they shall raise up the former desolations, and they shall repair the waste cities, the desolations of many generations.” They shall be called kingdom priests, and the people will know them as ministers of God.

The gospel can lift this destroying burden from the mind, give beauty for ashes, and the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness. But unless the weight of the burden is felt the gospel can mean nothing to the man; and until he sees a vision of God high and lifted up, there will be no woe and no burden. Low views of God destroy the gospel for all who hold them.

— A.W. Tozer

——

WHO GIVES THIS WORD? It is a word to mourners in Zion, meant for their consolation. But who gives it? The answer is not far to seek. It comes from him who said, “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me,” “he hath sent me to bind up the broken-hearted.” Now, in a very inferior and subordinate sense, Christian ministers have the Spirit of God resting upon them, and they are sent to bind up the broken-hearted; but they can only do so in the name of Jesus, and in strength given from him. This word is not spoken by them, nor by prophets or apostles either, but by the great Lord and Master of apostles and prophets, and ministers, even by Jesus Christ himself. If he declares that he will comfort us, then we may rest assured we shall be comforted! The stars in his right hand may fail to penetrate the darkness, but the rising of the Sun of Righteousness effectually scatters the gloom. If the consolation of Israel himself comes forth for the uplifting of his downcast people, then their doubts and fears may well fly apace, since his presence is light and peace.

But, who is this anointed one who comes to comfort mourners? He is described in the preface to the text as a preacher. “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath appointed me to preach good tidings unto the meek.” Remember what kind of preacher Jesus was. “Never man spake like this man.” He was a son of consolation indeed. It was said of him, “A bruised reed shall he not break, and the smoking flax shall he not quench.” He was gentleness itself: his speech did not fall like a hail shower, it dropped like the rain, and distilled as the dew, as the small rain upon the tender herb. He came down like the soft vernal shower upon the new-mown grass, scattering refreshment and revival wherever his words were heard. The widow at the gates of Nain dried her eyes when he spake, and Jairus no longer mourned for his child. Magdalene gave over weeping, and Thomas ceased from doubting, when Jesus showed himself. Heavy hearts leaped for joy, and dim eyes sparkled with delight at his bidding. Now, if such be the person who declares he will comfort the broken-hearted, if he be such a preacher, we may rest assured he will accomplish his work.

In addition to his being a preacher, he is described as a physician. “He hath sent me to bind up the broken-hearted.” Some hearts want more than words. The choicest consolations that can be conveyed in human speech will not reach their case; the wounds of their hearts are deep, they are not flesh cuts, but horrible gashes which lay bare the bone, and threaten ere long to kill unless they be skilfully closed. It is, therefore, a great joy to know that the generous friend who, in the text, promises to deal with the sorrowing, is fully competent to meet the most frightful cases. Jehovah Rophi is the name of Jesus of Nazareth; he is in his own person the Lord that healeth us. He is the beloved physician of men’s souls. “By his stripes we are healed.” Himself took our infirmities, and bare our sicknesses, and he is able now with a word to heal all our diseases, whatever they may be. Joy to you, ye sons of mourning; congratulation to you, ye daughters of despondency: he who comes to comfort you can not only preach with his tongue, but he can bind up with his hand. “He healeth the broken in heart, and bindeth up their wounds. He telleth the number of the stars; he calleth them all by their names.”

As if this were not enough, our gracious helper is next described as a liberator. “He hath sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound.” There were many downcast persons in Israel in the olden times—persons who had become bankrupt, and, therefore, had lost their estates, and had even sunk yet further into debt, till they were obliged to sell their children into slavery, and to become themselves bondsmen. Their yoke was very heavy, and their trouble was very sore. But the fiftieth year came round, and never was there heard music so sweet in all Judea’s land, as when the silver trumpet was taken down on the jubilee morn, and a loud shrill blast was blown in every city, and hamlet, and village, in all Israel, from Dan even to Beer-sheba. What meant that clarion sound? It meant this: “Israelite, thou art free. If thou hast sold thyself, go forth without money for the year of jubilee has come.” Go back, go back, ye who have lost your lands; seek out the old homestead, and the acres from whence ye have been driven: they are yours again. Go back, and plough, and sow, and reap once more, and sit each man under his vine and his fig-tree, for all your heritages are restored. This made great joy among all the tribes, but Jesus has come with a similar message. He, too, publishes a jubilee for bankrupt and enslaved sinners. He breaks the fetters of sin, and gives believers the freedom of the truth. None can hold in captivity the souls whom Jesus declares to be the Lord’s free men.

Surely, if the Savior has power, as the text declares, to proclaim liberty to the captive, and if he can break open prison doors, and set free those convicted and condemned, he is just the one who can comfort your soul and mine, though we be mourning in Zion. Let us rejoice at his coming, and cry Hosanna, blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord. Happy are we that we live in an age when Jesus breaks the gates of brass and cuts the bars of iron in sunder.

As if this were not all and not enough, one other matter is mentioned concerning our Lord, and he is pictured as being sent as the herald of good tidings of all sorts to us the sons of men. Read the second verse: “To proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.” God has taken upon himself human flesh. The infinite Jehovah came down from heaven and became an infant, lived among us, and then died for us. Behold in the person of the incarnate God the sure pledge of divine benevolence. “He that spared not his own Son, but freely delivered him up for us all, how shall he not with him also freely give us all things?” Beloved, the very fact that a Savior came to the world should be a source of hope to us, and when we think what a Savior he was, how he suffered, how he finished the work that was given him to do, and what a salvation it is which he has wrought out for us, we may well feel that the comfort of mourners is work for which he is well suited, and which he can execute most effectually. How beautiful upon Olivet and Calvary are the feet of him that bringeth, in his person and his world “good tidings, that publisheth peace, that bringeth good tidings of good, that publisheth salvation.” But I must not linger. I have spoken of you enough to lead your thoughts to the blessed person who here declares that he will comfort the mourner. May the Holy Ghost reveal him unto you in all the power of his arm, the love of his heart, the virtue of his blood, the prevalence of his plea, the majesty of his exaltation, and the glory of his character.

[…]

III. What is that, then, in the third place, WHICH IS SPOKEN in the text to those that mourn? I would draw particular attention to the words here, “To appoint unto them that mourn in Zion, to give unto them beauty for ashes.” Come, mourning souls, who mourn in the way described, come ye gladly hither: there is comfort appointed for you, and there is also comfort given to you. It is the prerogative of King Jesus both to appoint and to give. How cheering is the thought that as our griefs are appointed, so also are our consolations. God has allotted a portion to every one of his mourners, even as Joseph allotted a mess to each of his brethren at the feast. You shall have your due share at the table of grace, and if you are a little one, and have double sorrows, you shall have a double portion of comfort. “To appoint unto them.” This is a word full of strong consolation; for if God appoints me a portion, who can deprive me of it? If he appoints my comfort, who dare stand in the way? If he appoints it, it is mine by right. But then, to make the appointment secure, he adds the word “To give.” The Holy One of Israel in the midst of Zion gives as well as appoints. The rich comforts of the gospel are conferred by the Holy Spirit, at the command of Jesus Christ, upon every true mourner in the time when he needs them; they are given to each spiritual mourner in the time when he would faint for lack of them. He can effectually give the comfort appointed for each particular case. All I can do is to speak of the comfort for God’s mourners. I can neither allot it, nor yet distribute it; but our Lord can do both. My prayer is that he may do so at this moment; that every holy mourner may have a time of sweet rejoicing while siting at the Master’s feet in a waiting posture. Did you never feel, while cast down, on a sudden lifted up, when some precious promise has come home to your soul? This is the happy experience of all the saints.

“Sometimes a light surprises

The Christian while he sings:

It is the Lord who rises

With healing in his wings.

When comforts are declining,

He grants the soul again,

A season of clear shining

To cheer it, after rain.”

Our ever gracious and almighty Lord knows how to comfort his children, and be assured he will not leave them comfortless. He who bids his ministers again and again attend to this duty, and says, “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people,” will not himself neglect to give them consolation. If you are very heavy, there is the more room for the display of his grace in you, by making you very joyful in his ways. Do not despair; do not say, “I have fallen too low, my harp has been so long upon the willows that it has forgotten Zion’s joyful tunes.” Oh, no, you shall lay your fingers amongst the old accustomed strings, and the art of making melody shall come back to you, and your heart shall once more be glad. He appoints and he gives—the two words put together afford double hope to us—he appoints and he gives comfort to his mourners.

Observe, in the text, the change Christ promises to work for his mourners. First, here is beauty given for ashes. In the Hebrew there is a ring in the words which cannot be conveyed in the English. The ashes that men put upon their head in the East in the time of sorrow made a grim tiara for the brow of the mourner; the Lord promises to put all these ashes away, and to substitute for them a glorious head dress—a diadem of beauty. Or, if we run away from the word, and take the inner sense, we may look at it thus:—mourning makes the face wan and emaciated, and so takes away the beauty; but Jesus promises that he will so come and reveal joy to the sorrowing soul, that the face shall fill up again: the eyes that were dull and cloudy shall sparkle again, and the countenance, yea, and the whole person shall be once more radiant with the beauty which sorrow had so grievously marred. I thank God I have sometimes seen this change take place in precious saints who have been cast down in soul. There has even seemed to be a visible beauty put upon them when they have found peace in Jesus Christ, and this beauty is far more lovely and striking, because it is evidently a beauty of the mind, a spiritual lustre, far superior to the surface comeliness of the flesh. When the Lord shines full upon his servants’ faces, he makes them fair as the moon, when at her full she reflects the light of the sun. A gracious and unchanging God sheds on his people a gracious and unfading loveliness. O mourning soul, thou hast made thine eyes red with weeping, and thy cheeks are marred with furrows, down which the scalding tears have burned their way; but the Lord that healeth thee, the Lord Almighty who wipeth all tears from human eyes, shall visit thee yet; and, if thou now believes “in Jesus, he shall visit thee now, and chase these cloudy griefs away, and thy face shall be bright and clear again, fair as the morning, and sparkling as the dew. Thou shalt rejoice in the God of thy salvation, even in God, thy exceeding joy. Is not this a dainty promise for mourning souls?

Then, it is added, “He will give the oil of joy for mourning.” Here we have first beauty, and then unction. The Orientals used rich perfumed oils on their persons—used them largely and lavishly in times of great joy. Now, the Holy Spirit comes upon those who believe in Jesus, and gives them an anointing of perfume, most precious, more sweet and costly than the herd of Araby. An unction, such as royalty has never received, sheds its costly moisture over all the redeemed when the Spirit of the Lord rests upon them. “We have an unction from the Holy One,” saith the apostle. “Thou anointest my head with oil, my cup runneth over.” Oh, how favored are those who have the Spirit of God upon them! You remember that the oil which was poured on Aaron’s head went down to the skirts of his garment, so that the same oil was on his skirts that had been on his head. It is the same Spirit that rests on the believer as that which rests on Jesus Christ, and he that is joined unto Christ is one Spirit. What favor is here! Instead of mourning, the Christian shall receive the Holy Spirit, the Comforter who shall take of the things of Christ, and reveal them unto him, and make him not merely glad, but honored and esteemed.

Then, it is added, to give still greater fullness to the cheering promise, that the Lord will give “the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness.” The man is first made beautiful, next he has the anointing, then afterwards he is arrayed in robes of splendor. What garments these are! Surely Solomon in all his glory wore not such right royal apparel. “The garment of praise.” what a dress is this! Speak of wrought gold, or fine linen, or needlework of divers colors, or taffeta, or damasks, or gorgeous silks most rich and rare which come from far off lands—where is anything compared with “the garment of praise?” When a man wraps himself about, as it were, with psalmody, and lives for ever a chorister, singing not with equal voice, but with the same earnest heart as they do who day and night keep up the never ending hymn before the throne of the infinite! As, what a life is his, what a man is he! O mourner, this is to be your portion; take it now; Jesus Christ will cover you, even at this hour, with the garment of praise; so grateful shall you be for sins forgiven, for infirmity overcome, for watchfulness bestowed, for the church revived, for sinners saved, that you shall undergo the greatest conceivable change, and the sordid garments of your woe shall be put aside for the brilliant array of delight. It shall not be the spirit of praise for the spirit of heaviness, though that were a fair exchange, but as your heaviness you tried to keep to yourself, so your praise you shall not keep to yourself, it shall be a garment to you, external and visible, as well as inward and profound. Wherever you are it shall be displayed to others, and they shall see and take knowledge of you that God has done great things for you whereof you are glad. I wish I had power to speak fitly on such a theme as this; but, surely, it needs him upon whom the Spirit rested without measure to proclaim this joyful promise to the mourners in Zion.

We must close, by noticing what will be the result of this appointment, and text concludes, by saying, “That they might be called trees of righteousness, the planting of the Lord, that he might be glorified.” We learn, here, that those mourning souls who are cast down, and have put ashes on their heads, shall, when Jesus Christ in infinite mercy comes to them, be made like trees—like “oaks;” the original is, like “oaks of righteousness,” that is, they shall become strong, firmly rooted, covered with verdure; they shall be like a well-watered tree for pleasantness and delight. Thou sayest, “I am a dry tree, a sere branch, I am a cast off, fruitless bough; Oh that I were visited of God and saved! I mourn because I cannot be what I would.” Mourner, thou shalt be all thou wouldst be, and much more if Jesus visits thee. Breathe the prayer to him now; look to him, trust him. He can change thee from a withered tree that seems twice dead into a tree standing by the rivers of water, whose leaf is unwithering, and whose fruit ripens in its season. Only have confidence in an anointed Savior, rely upon him who came not here to destroy but to bless, and thou shalt yet through faith become a tree of righteousness, the planting of the Lord, that he may be glorified.

But, the very pith of the text lies in a little word to which you must look. “Ye shall be called trees of righteousness.” Now, there are many mourning saints who are trees of righteousness, but nobody calls them so, they are so desponding that they give a doubtful idea to others. Observers ask, “Is this a Christian?” And those who watch and observe them are not at all struck with their Christian character. Indeed, I may be speaking to some here who are true believers in Jesus, but they are all their lifetime subject to bondage; they hardly know themselves whether they are saved, and, therefore, they cannot expect that others should be very much impressed by their godly character and fruitful conversation. But, O mourners! if Jesus visits you, and gives you the oil of joy, men shall call you “trees of righteousness,” they shall see grace in you, they shall not be able to help owning it, it shall be so distinct in the happiness of your life, that they shall be compelled to see it. I know some Christian people who, wherever they go, are attractive advertisements of the gospel. Nobody could be with them for a half an hour without saying, “Whence do they gain this calm, this peace, this tranquility, this holy delight and joy?” Many have been attracted to the cross of Christ by the holy pleasantness and cheerful conversation of those whom Christ has visited with the abundance of his love. I wish we were all such. I would not discourage a mourner; no, but encourage him to seek after the garments of praise; nevertheless, I must say that it is a very wretched thing for so many professors to go about the world grumbling at what they have and at what they have not, murmuring at the dispensations of providence, and at the labors of their brethren. They are more like wild crab-trees than the Lords fruit-trees. Well may people say, “If these are Christians, God save us from such Christianity.” But, when a man is contented—more than that, when he is happy under all circumstances, when “his spirit doth rejoice in God his Savior” in deep distress, when he can sing in the fires of affliction, when he can rejoice on the bed of sickness, when his shout of triumph grows louder as his conflict waxes more and more severe, and when he can utter the sweetest song of victory in his departing moments, then all who see such people call them trees of righteousness, they confess that they are the people of God.

Note, still, the result of all this goes further, “They shall he called trees of righteousness, the planting of the Lord,” that is to say, where there is joy imparted, and unction given from the Holy Spirit, instead of despondency, men will say, “It is God’s work, it is a tree that God has planted, it could not grow like that if anybody else had planted it; this man is a man of God’s making, his joy is a joy of God’s giving.” I feel sure that in the case of some of us we were under such sadness of heart before conversion, through a sense of sin, that when we did find peace, everybody noticed the change there was in us, and they said one to another, “Who has made this man so happy, for he was just now most heady and depressed?” And, when we told them where we lost our burden, they said, “Ah, there is something, in religion after all.” “Then said they among the heathen the Lord hath done great things for them.” Remember poor Christian in Pilgrim’s Progress. Mark what heavy sighs he heaved, what tears fell from his eyes, what a wretched man he was when he wrung his hands, and said, “The city wherein I dwell is to be burned up with fire from heaven, and I shall be consumed in it, and, besides, I am myself undone by reason of a burden that lieth hard upon me. Oh that I could get rid of it!” Do you remember John Bunyan’s description of how he got rid of the burden? He stood at the foot of the cross, and there was a sepulcher hard by, and as he stood and looked, and saw one hanging on the tree, suddenly the bands that bound his burden cracked, and the load rolled right away into the sepulcher, and when he looked for it, it could not be found. And what did he do? Why, he gave three great leaps for joy, and sang,

“Bless’d cross! bless’d sepulcher! bless’d rather

be the man that there was put to shame for me.”

If those who knew the pilgrim in his wretchedness had met him on the other side of that never-to-be-forgotten sepulcher, they would have said, “Are you the same man?” If Christiana had met him that day, she would have said, “My husband, are you the same? What a change has come over you;” and, when she and the children marked the father’s cheerful conversation, they could have been compelled to say, “It is the Lord’s doing, and it is wondrous in our eyes.” Oh live such a happy life that you may compel the most wicked man to ask where you learned the art of living. Let the stream of your life be so clear, so limpid, so cool, so sparkling, so like the river of the water of life above, that men may say, “Whence came this crystal rivulet? We will trace it to its source,” and so may they be led to the foot of that dear cross where all your hopes began.

Another word remains, and when we have considered it, we will conclude. That other word is this, “The planting of the Lord, that he might be glorified.” That is the end of it all, that is the great result we drive at, and that is the object even of God himself, “that he might be glorified.” For when men see the cheerful Christian, and perceive that this is God’s work, then they own the power of God; not always, perhaps, with their hearts as they should, but still they are obliged to confess “this is the finger of God.” Meanwhile, the saints, comforted by your example, praise and bless God, and all the church lifts up a song to the Most High. Come, my brethren and sisters, are any of you down; are you almost beneath the enemy’s foot? Here is a word for you, “Rejoice not over me, O mine enemy, though I fall yet shall I rise again.” Are any of you in deep trouble—very deep trouble? Another word then for you; “When thou passest through the waters, I will be with thee, and through the rivers, they shall not overflow thee: when thou walkest through the fire, thou shalt not be burned; neither shall the flame kindle upon thee.” Are you pressed with labors and afflictions? “As thy days so shall thy strength be,” “All things work together for good to them that love God, to them that are the called according to his purpose.” Are you persecuted? Here is a note of encouragement for you: “Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad; for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.” Whatever your circumstances are, “Rejoice in the Lord always, and again I say rejoice.” Think what Jesus has given you, your sins are pardoned for his name sake, your heaven is made secure to you, and all that is wanted to bring you there; you have grace in your hearts, and glory awaits you; you have already grace within you, and greater grace shall be granted you; you are renewed by the Spirit of Christ in your inner man the good work is begun, and God will never leave it till he has finished it; your names are in his book, nay, graven on the palms of his hands; his love never changes, his power never diminishes, his grace never fails, his truth is firm as the hills, and his faithfulness is like the great mountains. Lean on the love of his heart, on the might of his arm, on the merit of his blood, on the power of his plea, and the indwelling of his Spirit. Take such promises as these for your consolation, “Strengthen ye the weak hands, and confirm the feeble knees. Say to them that are of a fearful heart, be strong, fear not.” “Fear not, thou worm Jacob, and ye men of Israel; I will help thee, saith the Lord, and thy Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel.” “For a small moment have I forsaken thee; but with great mercies will I gather thee. In a little wrath I hid my face from thee for a moment; but with everlasting kindness will I have mercy on thee, saith the Lord thy Redeemer. For this is as the waters of Noah unto me: for as I have sworn that the waters of Noah should no more go over the earth; so have I sworn that I would not be wroth with thee, nor rebuke thee. For the mountains shall depart, and the hills be removed; but my kindness shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of my peace be removed, saith the Lord that hath mercy on thee.” “My grace is sufficient for thee, for my strength is made perfect in weakness.” “He giveth power to the faint; and to them that have no might he increaseth strength.” “The eternal God is thy refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms: and he shall thrust out the enemy from before thee; and shall say, destroy them.” “I am God, I fail not, therefore ye sons of Jacob are not consumed.” One might continue for ever quoting these precious passages, but may the Lord apply one or other of them to every mourner’s soul; and, especially if there be a mourning sinner here, may he get a grip of that choice word, “Him that cometh to me I will in no wise cast out;” or, that other grand sentence, “All manner of sin and blasphemy shall be forgiven unto men;” or, that other, “The blood of Jesus Christ, his Son, cleanseth us from all sin:” or, that equally encouraging word, “Come now, and let us reason together; though your sins be as scarlet they shall be as wool, though they be red like crimson they shall be as snow.” The Lord bring us all into comfort and joy by the way of the cross.

Peradventure, I speak to some for whom the promises of God have no charm; let me, then, remind them that his threatenings are as sure as his promises. He can bless, but he can also curse. Be appoints mourning for those who laugh now with sinful merriment; he will give to his enemies vengeance for all their rebellions. He has himself said, “And it shall come to pass, that instead of sweet smell there shall be stink; and instead of a girdle a rent; and instead of well set hair baldness; and instead of a stomacher a girding of sackcloth; and burning instead of beauty.” Beware, then, ye that forget God, lest he overthrow you in his hot displeasure. Seek ye the Savior now, lest the acceptable year of the Lord be closed with a long winter of utter despair.

“Ye who spurn his righteous sway,

Yet, oh yet, he spares your breath;

Yet his hand, averse to slay,

Balances the bolt of death.

Ere that dreadful bolt descends,

Haste before his feet to fall,

Kiss the scepter he extends,

And adore him, ‘Lord of all.'”

Source: Sermon: Beauty For Ashes by Charles Spurgeon

Photo Credits: Sebastião Salgado “Genesis”